Ahoy! From Picardy review: melancholic dioramic storytelling

This elegantly crafted dioramic experience (available on Apple Vision Pro) follows a scientist who’s alone and forlorn on an island, which was once an exquisite place of refuge but is now barren and drought-stricken. Most of the time we see the titular character in Ahoy! From Picardy from a distance, and yet, the tone feels intimate and reflective—like we’re sharing this little fellow’s journey. There are lots of lovely touches, including the structure of the environment in which it unfolds: a dome-like space that looks like a massive snow globe, about the size of a small table.

Initially this literal storytelling sphere is opaque, an animated prologue projected onto its curved edges, zhushing up a fairly rote introduction with some visual pop. The narrator declares that “there are some islands that have been forgotten from the maps, while others have been deleted,” a sentence that brings to mind old stories about lost ruins and forgotten civilisations. Though it’s a little marred by that ugly final world, “deleted,” which goes against the hopeful grain of the experience by suggesting irretrievable lost.

Director: Daniel Jones

Release date: February, 2025

Available on: Apple Vision Pro

Experienced on: Apple Vision Pro

We’re informed that Picardy lived on one of these islands, once filled with magnificent trees and fauna, before the rain stopped and a drought came. He decided to adapt to the times and become, as you do, a rainmaker, trying his darndest to summon sweet, sweet drops of H20. But one of his experiments went terribly wrong, creating a fire that destroyed all the trees and forced him off the island. When Picardy learns of a new scientific breakthrough in Paris—one that can indeed summon rain—he decides to get the island into better shape, and return the plants to life.

When the prologue concludes, the dome’s opaque edges fade away and reveal a table-like surface, onto which most of the production’s 16-ish minute runtime unfolds. We see the island and a lab where Picardy works, tinkering away on his research, trying to get a twig to grow. Sometimes the aforementioned surface spins around like a lazy Susan, rearranging the composition; these lovely transitions respect the spatial consistency of the scene, resisting the film-centric grammar of cuts. By contrast, when director Daniel Jones doesn’t resist cutting—jumping back spatially in more conventional reconfigurations—the effect feels sharp, almost displacing.

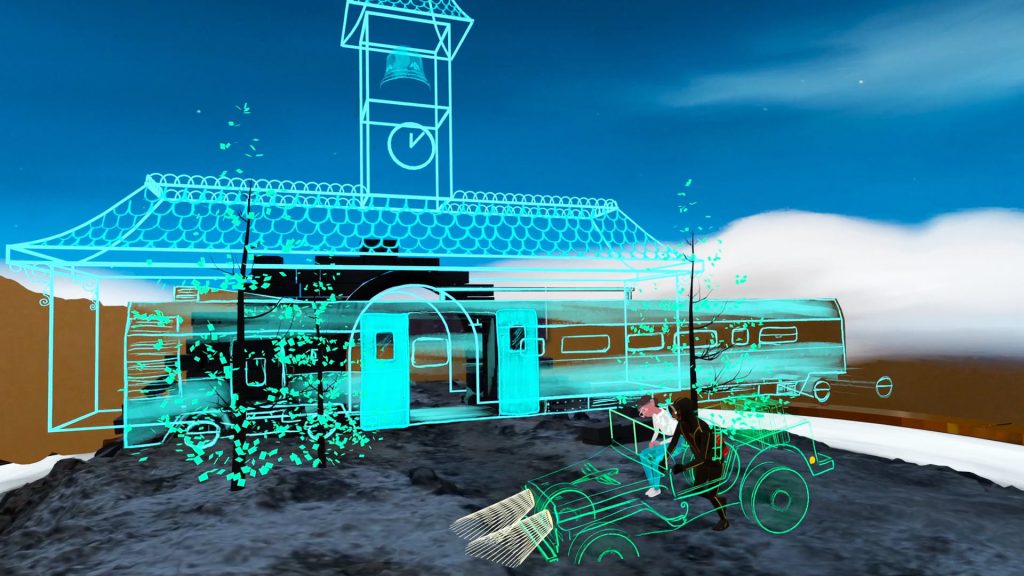

Acoustic, lyrical songs set a ponderous tone. There are some splashes of light interactivity—so light (such as touching an object to progress the story) they border on superfluous. In one striking moment, Picardy traverses the island’s rocky terrain while elements of Paris—including streetlights and statues—pop up around him, rendered in transparent chalk-like form. This environment is not really Paris, and no longer just the island; it’s been gently dislodged from reality, repositioned in a dreamy space between actual and virtual.

This experience reminded me of Allumette—another quaintly toned, narrative-driven dioramic production that takes place in a spatially contained otherworldly setting (a city in the clouds). I showed many people Allumette shortly after it arrived, circa 2016, back when the ability to step into, and through, the viewing space was a big novelty—to be inside the story—as was the ability to rearrange scale and perspective. As I wrote in my review: “our ability to walk forward and stick our faces right up to the characters allows us, in cinematic terms, to transform the equivalent of a long shot into the equivalent of a close-up. The reverse of course applies when the observer takes a step back, in effect turning close-ups into longshots.”

Since then, that novelty has worn off—at least for people like me who became accustomed to spatial experiences that allow these sorts of rearrangements. One problematic aspect of Allumette was that it gave viewers too much liberation—too much flexibility, visually speaking. There’s a big moment toward the end when a dramatic explosion takes place, which is hugely important to the narrative, yet some people I showed the experience to missed this crucial moment because they were looking in the wrong direction.

Spatial storytellers have learned a lot from those early experiences. You can’t miss the ending of Ahoy! From Picardy. Though this comes at a cost: the appearance of a rectangular screen towards the conclusion, which projects an epilogue, felt a bit like cheating, disconnected from the rest of the experience. But that’s a minor quibble. This is a memorable, gracefully crafted production that tells a gently melancholic story.